Linux 基础IO-从 “一切皆文件” 到自定义 libc 缓冲区

前言

在 C 语言文件操作的学习中,我们常会遇到两个 “绕不开” 的核心问题:为什么说操作系统中 “一切皆文件”?

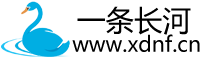

printf、fwrite这些库函数比系统调用write更高效的秘密是什么?这两个问题的答案,其实都指向同一个关键概念 ——缓冲区。很多开发者对文件操作的认知停留在 “调用函数读写数据” 的表层,却忽略了缓冲区的存在:它是 libc 库(C 标准库)为提升性能设计的 “中间层”,也是连接用户代码与系统内核的重要桥梁。而 “一切皆文件” 的理念,则为键盘、显示器、磁盘文件等不同设备提供了统一的操作接口,让缓冲区的复用成为可能。

本文将从 “一切皆文件” 的底层逻辑切入,逐步拆解缓冲区的本质、引入原因与三种缓冲类型,再通过实际现象观察验证缓冲机制的存在。最终,我们会亲手设计一个简化版的 libc 文件操作库(包含

mystdio.h头文件、mystdio.c实现与usercode.c测试代码),让你从 “使用者” 转变为 “设计者”,彻底理解 C 语言文件操作的底层逻辑。无论你是刚接触文件操作的新手,还是想夯实底层基础的开发者,都能在本文中找到清晰的答案。

目录

理解“一切皆文件”

什么是缓冲区

为什么要引入缓冲区机制

缓冲类型

现象观察

FILE

简单设计一下libc库

mystdio.h

mystdio.c

usercode.c

理解“一切皆文件”

首先,在windows中是文件的东西,它们在linux中也是文件;其次一些在windows中不是文件的东西,比如进程、磁盘、显示器、键盘这样硬件设备也被抽象成了文件,你可以使用访问文件的方法访问它们获得信息;甚至管道,也是文件;网络编程中的socket(套接字)这样的东西, 使用的接口跟文件接口也是一致的。这样做最明显的好处是,开发者仅需要使用一套 API 和开发工具,即可调取 Linux 系统中绝大部分的资源。举个简单的例子,Linux 中⼏乎所有读(读文件,读系统状态,读PIPE)的操作都可以用read 函数来进行;几乎所有更改(更改文件,更改系统参数,写 PIPE)的操作都可以用 write 函数来进行。

struct file {

...

struct inode *f_inode; /* cached value */

const struct file_operations *f_op;

...

atomic_long_t f_count; // 表⽰打开⽂件的引⽤计数,如果有多个⽂件指针指向

它,就会增加f_count的值。

unsigned int f_flags; // 表⽰打开⽂件的权限

fmode_t f_mode; // 设置对⽂件的访问模式,例如:只读,只写等。所有的标志在头⽂件<fcntl.h> 中定义

loff_t f_pos; // 表⽰当前读写⽂件的位置

...

} __attribute__((aligned(4))); /* lest something weird decides that 2 is OK */struct file_operations {

struct module *owner;

//指向拥有该模块的指针;

loff_t (*llseek) (struct file *, loff_t, int);

//llseek ⽅法⽤作改变⽂件中的当前读/写位置, 并且新位置作为(正的)返回值.

ssize_t (*read) (struct file *, char __user *, size_t, loff_t *);

//⽤来从设备中获取数据. 在这个位置的⼀个空指针导致 read 系统调⽤以 -

EINVAL("Invalid argument") 失败. ⼀个⾮负返回值代表了成功读取的字节数( 返回值是⼀个

"signed size" 类型, 常常是⽬标平台本地的整数类型).

ssize_t (*write) (struct file *, const char __user *, size_t, loff_t *);

//发送数据给设备. 如果 NULL, -EINVAL 返回给调⽤ write 系统调⽤的程序. 如果⾮负, 返

回值代表成功写的字节数.

ssize_t (*aio_read) (struct kiocb *, const struct iovec *, unsigned long,

loff_t);

//初始化⼀个异步读 -- 可能在函数返回前不结束的读操作.

ssize_t (*aio_write) (struct kiocb *, const struct iovec *, unsigned long,

loff_t);

//初始化设备上的⼀个异步写.

int (*readdir) (struct file *, void *, filldir_t);

//对于设备⽂件这个成员应当为 NULL; 它⽤来读取⽬录, 并且仅对**⽂件系统**有⽤.

unsigned int (*poll) (struct file *, struct poll_table_struct *);

int (*ioctl) (struct inode *, struct file *, unsigned int, unsigned long);

long (*unlocked_ioctl) (struct file *, unsigned int, unsigned long);

long (*compat_ioctl) (struct file *, unsigned int, unsigned long);

int (*mmap) (struct file *, struct vm_area_struct *);//mmap ⽤来请求将设备内存映射到进程的地址空间. 如果这个⽅法是 NULL, mmap 系统调⽤返

回 -ENODEV.

int (*open) (struct inode *, struct file *);

//打开⼀个⽂件

int (*flush) (struct file *, fl_owner_t id);

//flush 操作在进程关闭它的设备⽂件描述符的拷⻉时调⽤;

int (*release) (struct inode *, struct file *);

//在⽂件结构被释放时引⽤这个操作. 如同 open, release 可以为 NULL.

int (*fsync) (struct file *, struct dentry *, int datasync);

//⽤⼾调⽤来刷新任何挂着的数据.

int (*aio_fsync) (struct kiocb *, int datasync);

int (*fasync) (int, struct file *, int);

int (*lock) (struct file *, int, struct file_lock *);

//lock ⽅法⽤来实现⽂件加锁; 加锁对常规⽂件是必不可少的特性, 但是设备驱动⼏乎从不实现

它.

ssize_t (*sendpage) (struct file *, struct page *, int, size_t, loff_t *,

int);

unsigned long (*get_unmapped_area)(struct file *, unsigned long, unsigned

long, unsigned long, unsigned long);

int (*check_flags)(int);

int (*flock) (struct file *, int, struct file_lock *);

ssize_t (*splice_write)(struct pipe_inode_info *, struct file *, loff_t *,

size_t, unsigned int);

ssize_t (*splice_read)(struct file *, loff_t *, struct pipe_inode_info *,

size_t, unsigned int);

int (*setlease)(struct file *, long, struct file_lock **);

};

什么是缓冲区

为什么要引入缓冲区机制

缓冲类型

多次printf以及其他函数的数据放到语言层缓冲区,后面只需要一次刷新,调用一次系统调用就可以写到文件中。

数据交给系统,交给硬件 ---本质全是拷贝!!!

计算器数据流动的本质 :一切皆拷贝!!!

现象观察

close(1);

int fd1=open("log1.txt",O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_APPEND,0666);

if(fd1<0) exit(1);

printf("fd1:%d\n",fd1);

printf("hello C!\n");

printf("hello C!\n");

close(fd1);

当加入close(fd1),关闭文件后,发现没有写入log1.txt

用write就写进去了。文件描述符关不关闭无所谓。

根据前面的知识,printf是库函数,write是系统调用

我们在关闭前可以fflush一下。

大致可以理解,在文件描述符关闭之前,用户没有刷新等操作,没有进行下一步,且文件描述符关闭后,就不能通过系统调用进行刷新到文件缓冲区。

像fopen,fflush 都提到了FILE*,C语言中,一个文件,都要有自己的缓冲区。

我们提到的printf,fprintf,fputs等都与stdout有关,而stdout也是FILE*类型的。

而FILE是C语言的一个结构体,里面封装了文件描述符,和缓冲区。

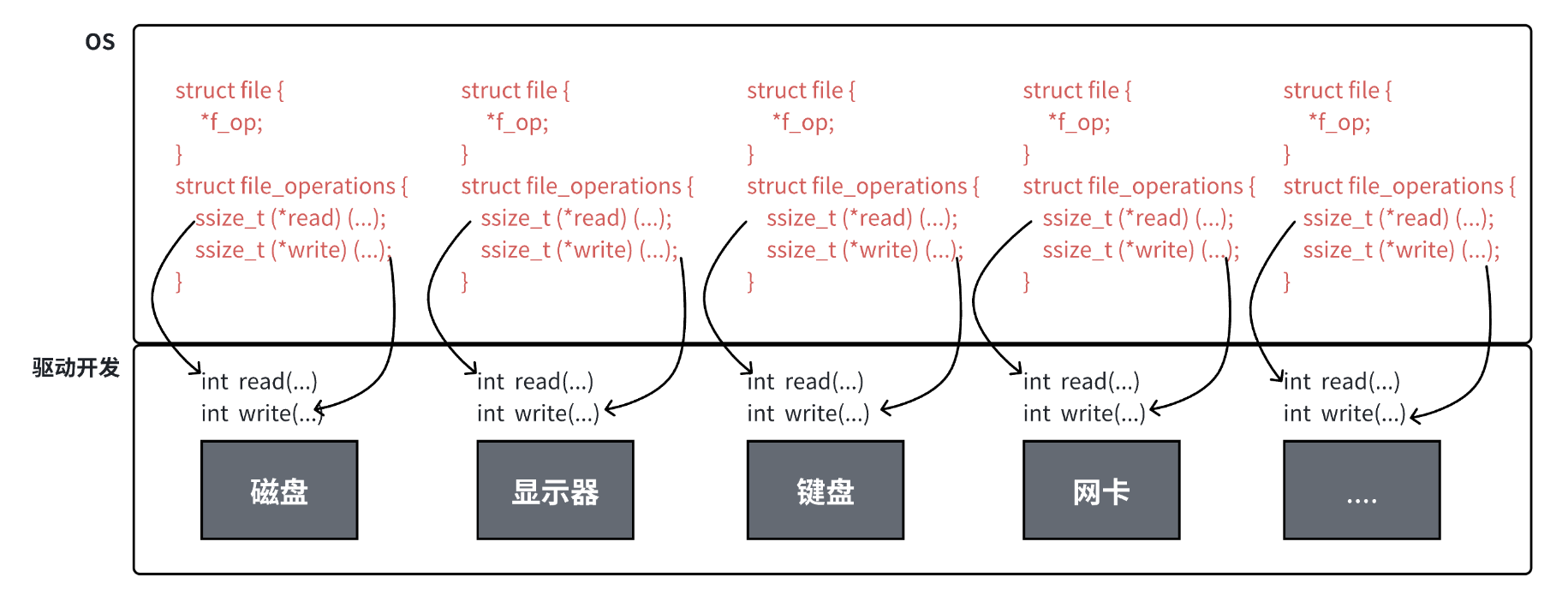

FILE

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

const char *msg0="hello printf\n";

const char *msg1="hello fwrite\n";

const char *msg2="hello write\n";

printf("%s", msg0);

fwrite(msg1, strlen(msg1), 1, stdout);

write(1, msg2, strlen(msg2));

fork();

return 0;

}

综上: printf fwrite 库函数会自带缓冲区,而 write 系统调用没有带缓冲区。另外,我们这里所说的缓冲区,都是用户级缓冲区。其实为了提升整机性能,OS也会提供相关内核级缓冲区,不过不再我们讨论范围之内。那这个缓冲区谁提供呢? printf fwrite 是库函数, write 是系统调用,库函数在系统调用的“上层”, 是对系统调用的“封装”,但是 write 没有缓冲区,而 printf fwrite 有,足以说明,该缓冲区是二次加上的,又因为是C,所以由C标准库提供。

简单设计一下libc库

mystdio.h

#pragma once #include <stdio.h>#define MAX 1024

#define NONE_FLUSH (1<<0)

#define LINE_FLUSH (1<<1)

#define FULL_FLUSH (1<<2)

typedef struct IO_FILE{int fileno;int flag;char outbuffer[MAX];int bufferlen;int flush_method;}MyFile;MyFile *MyFopen(const char*path,const char*mode);void MyFclose(MyFile*);int MyFwrite(MyFile *,void *str,int len);void MyFFlush(MyFile*);

mystdio.c

1 #include "mystdio.h"2 #include <sys/types.h>3 #include <sys/stat.h>4 #include <fcntl.h>5 #include <string.h>6 #include <stdlib.h>7 #include <unistd.h>8 9 static MyFile *BuyFile(int fd,int flag){10 MyFile *f=(MyFile*)malloc(sizeof(MyFile));11 if(f==NULL) return NULL;12 f->bufferlen=0;13 f->fileno=fd;14 f->flag=flag;15 f->flush_method=LINE_FLUSH;16 memset(f->outbuffer,0,sizeof(f->outbuffer));17 return f;18 }19 MyFile *MyFopen(const char*path,const char*mode){20 int fd=-1;21 int flag=0;22 if(strcmp(mode,"w")==0){23 flag=O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC;24 fd=open(path,flag,0666);25 26 }27 else if(strcmp(mode,"a")==0){28 flag=O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_APPEND;29 fd=open(path,flag,0666);30 }31 else if(strcmp(mode,"r")==0){32 flag= O_RDWR;33 fd=open(path,flag);34 }35 else{3637 } 38 if(fd<0) return NULL;39 return BuyFile(fd,flag);40 }41 void MyFclose(MyFile* file){42 if(file->fileno <0 )return;43 MyFFlush(file);44 close(file->fileno);45 free(file);46 47 }48 int MyFwrite(MyFile *file,void *str,int len){49 //拷贝50 memcpy(file->outbuffer+file->bufferlen,str,len);51 file->bufferlen+=len;52 //尝试判断是否满足刷新条件53 if(file->flush_method & LINE_FLUSH && file->outbuffer[file->bufferlen-1]=='\n'){54 MyFFlush(file);55 }56 return 0;57 }58 void MyFFlush(MyFile* file){59 if(file->bufferlen <0) return ;60 int n=write(file->fileno,file->outbuffer,file->bufferlen);61 (void)n;62 fsync(file->fileno);63 file->bufferlen=0;64 }

usercode.c

1 #include <string.h>2 #include "mystdio.h"3 #include <unistd.h>4 int main()5 {6 MyFile* filep=MyFopen("./log.txt","a");7 if(!filep){8 printf("fopen error!\n");9 return 1;10 }11 int cnt=6;12 while(cnt--){13 //char *msg="hello myfile !\n"; 14 char *msg="hello myfile !!!";15 MyFwrite(filep,msg,strlen(msg));16 MyFFlush(filep);17 printf("buffer:%s\n",filep->outbuffer);18 sleep(1);19 }20 MyFclose(filep);21 return 0;22 }

当写入的字符串有“\n”和强制刷新时:

没有‘\n’和强制刷新:

有强制刷新但没有"\n"

结束语

从 “一切皆文件” 的统一接口,到缓冲区的性能优化,再到自定义 libc 库的实践,C 语言文件操作的核心逻辑始终围绕 “高效、统一” 两个关键词展开。缓冲区看似是 “额外的中间层”,实则是 libc 库平衡 “系统调用开销” 与 “用户操作便捷性” 的精妙设计;而 “一切皆文件” 的理念,则让这种设计能无缝适配键盘、显示器、磁盘等不同设备,极大降低了开发者的学习与使用成本。

通过亲手设计简化版

mystdio库,我们不仅理清了FILE结构体、缓冲策略、读写接口的实现逻辑,更能体会到 “从抽象到具体” 的编程思维 —— 日常使用的库函数并非 “黑箱”,只要拆解其核心模块,就能理解其设计本质。当然,真实的 libc 库(如 GNU C 库)远比我们设计的简化版复杂,还包含缓冲刷新策略、线程安全、错误处理等进阶功能,但本文搭建的 “框架” 已能覆盖核心逻辑。希望这篇文章能成为你理解 C 语言文件操作的 “敲门砖”,让你在后续使用或优化文件操作代码时,能从底层逻辑出发,做出更合理的选择。